On the nature of cytoplasm pt. 1: crowding & excluded volume

Usually when we do “in-vitro” experiments with purified proteins, AKA “biochemistry,” the only protein in the tube is the one we are studying. OK, perhaps the tube contains our favorite protein and a few others. But as you can see in the in the illustration below (a David Goodsell classic), cytosol is hardly dilute - it is BURSTING with protein, DNA and RNA. The cytosol of a bacterial, yeast or mammalian cell contains 2-4 million proteins per cubic micron, otherwise known as a whole lot of proteins that we were not planning to study.

One of the reasons to work with pure samples is that those other proteins can have specific effects on the one we are studying - binding, chemical modification, degradation, etc. - and we’d like to first get a baseline measurment of what our protein does on its own. But the concept of macromolecular crowding reverses this argument and says: most proteins do not naturally exist in dilute solutions, perhaps a concentrated protein solution has some generic (i.e. nonspecific) effect on the proteins we study?

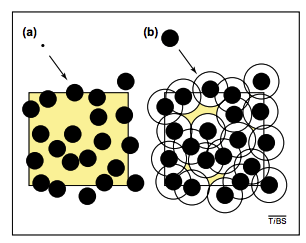

High protein concentration has a generic effect that is pretty easy to understand: because two non-interacting proteins can’t occupy the same physical space, one protein “excludes volume” for another. The extent of the “excluded volume effect” can be seen by comparing panels A & B in the figure above: a small molecule has relative freedom of motion in (A) but a larger molecule (e.g. a protein) cannot even approach other proteins due to its physical size (figure from this review by R. John Ellis). Crowding effectively reduces the volume of the solution, and it does this moreso for large molecules than small ones (hence the name “macromolecular crowding”). Somewhat unintuitively - because concentration equals molecules/volume (mols/liter units) - the effective concentration of a protein increases in a crowded solution because the volume that it can occupy decreases.

For clarity let’s try a little math. Suppose a protein \(A\) has a mass of 40 kDa and is roughly spherical. Let’s start by assuming that protein and water have the same density. This is not true - typical proteins are more dense than water - but this is a simple way to start because water has unit density of 1 g/mL. We can use this value to calculate the radius of \(A\) from its volume \(V = \frac{4}{3} \pi R^3\), which we can infer from its mass and density.

\[V = 40 \times 10^3 \frac{\text{g}}{\text{mol}} \times \frac{\text{mol}}{6.02 \times 10^{23} \text{protein}} \times 1 \frac{\text{mL}}{\text{g}} = 6.6 \times 10^{-20} \frac{\text{mL}}{\text{protein}}\]Since \(1 \text{mL} = 1 \text{cm}^3\)

\[R = \sqrt[3]{\frac{3 V}{4 \pi}} = 2.5 \times 10^{-7} \text{cm} = 2.5 \text{nm}\]This is actually about right for for a globular monomeric protein. Monomeric GFP, for example, is an oblong beta barrel protein of roughly 2x4 nm, meaning that its radius is 1-2 nm.

We can use this radius estimate to calculate the fraction of cytosolic volume that is filled with protein. Following the figure we’ll assume all the crowding agents are protein spheres the same size as \(A\). Since there are ~\(3 \times 10^6 \frac{\text{proteins}}{\text{fL cytosol}}\) and each protein occupies \(6.6 \times 10^{-20} \text{mL}\) then

\[3 \times 10^6 \times \frac{\text{proteins}}{\text{fL cytosol}} \times 10^{12} \frac{\text{fL}}{\text{mL}} \times 6.6 \times 10^{-20} \frac{\text{mL}}{\text{protein}} \simeq .2 \frac{\text{mL}}{\text{mL}}\]Meaning that the protein complement of cytosol occupies 15-25% of cell volume directly!

Notice, however, that this calculation ignores the effect summarized in the figure above from Ellis where the center of \(A\) can’t approach the boundary of a crowding protein. If we want to account for this effect we have to treat the crowding molecules as effectively being larger than their physical size, since the center of \(A\) must be at least one radius-length away.

Fortunately we assumed all the molecules were the same size so we can recalculate the volume of the crowding molecules assuming they have radius \(2R = 5 nm\) and, therefore

\[V' = \frac{4}{3} \pi (2R)^3 = 8V = 5.3 \times 10^{-19} \frac{\text{mL}}{\text{protein}}\]Plugging this number into the calculation above, we get a volume fraction of 1.59, meaning that 159% of the cytosolic volume is effectively occupied with protein! This is obviously nonsensical, but drives home the point that cytosol cannot be composed of average-sized protein monomers. Rather, a large fraction of cytosolic proteins must associate with each other in order to fit inside the cell. That is: crowding provides a very strong driving force for macromolecular association.

This calculation begs the question: how realistic are typical in-vitro experiments where proteins are examined in dilute solution? How far off could our measurements of binding and activity be? All this and more next time.

Thanks to Oliver Mueller-Cajar for suggesting this excellent review by R. John Ellis - “Macromolecular crowding: obvious but underappreciated”. I honestly hadn’t thought much about excluded volume or “macromolecular crowding” until I saw Ellis’ Figure 2 (above).