Just bury the algae?

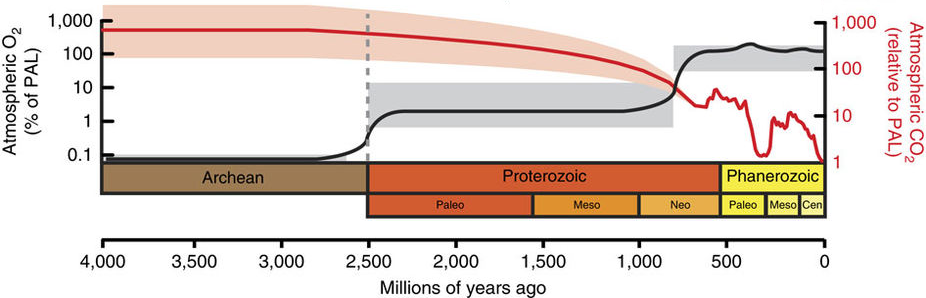

The word “fossil”, I think, conjurs images of dinosaurs. Maybe also fossilized leaves and coelacanths. Certainly I think of Littlefoot palling around verdant valleys, stream banks lined with cycads and ferns. But fossil fuels like petroleum are not formed from dinosaurs of course. They are mostly formed from algae, cyanobacteria and other small photosynthetic organisms that dominated Earth’s prehistory well before big reptiles and mammals entered the scene (Wikipedia has a fine summary). Coal is formed from land plants, mostly from trees. This realization prompts another thought: if algae and cyanobacteria (I’ll call them all “algae” here) fixed enough carbon to bring atmospheric CO2 levels from ~20% to somewhere near today’s low low partial pressure of 300-400 PPM (see Figure 1 of Shih et al. 2016 below) and, in so doing, made us all these incredible fuels to burn, then perhaps we could use the algae to suck all that carbon we are burning right back out of the air. After all, our present predicament (getting back to 300 ppm from 400 ppm) is much smaller than the historical effect of photosynthetic carbon fixation (going from 20% = 20000 ppm to 300 ppm). Maybe the algae can save us?

In this post I’ll try to take this idea seriously and ask: Is it plausible to grow algae at a great enough scale to negate human CO2 emissions? The general form of the idea is this:

- Grow a bunch of algae.

- Dry them or otherwise remove the water so we have what to drink.

- Bury them somewhere safe.

Before we dive in, I’ll try to dampen your expectations a bit with a few important points. While biological photosynthesis has wrought enormous changes on the Earth ecosystem, those changes took place over billions of years and entirely before the industrial revolution. So our problem today is very different. We have limited time, maybe tens of years, to reverse the effects of burning fossil fuels that accumulated over billions of years before human civilization began. Another important thing to remember is that growing algae at scale requires energy input. Algae are typically grown in ponds, glass containers or plastic bags. In any case, they need to be mixed (e.g. with electric paddles), supplied with nutrients and perhaps gasses (mostly CO2) for optimal growth. All of these inputs demand energy (to run motors and pumps, to make and transport nutrients like ammonia). If this energy is drawn from a source that produces CO2 emissions it would be super counter-productive. These realizations sharpen our question, which we can phrase as such: Is it possible to grow algae in such a way that the net result is to fix as much carbon in a year as humans emit?

TL;DR

The main takeaway is that there is currently not enough non-emissive power on Earth to grow enough algae to ameliorate all human emissions. However, the solar energy incident on Earth is, in principle, more than sufficient for the task. It is possible that, through a combination of strategies, this approach to climate remediation could be made feasible. These strategies certainly include (but are not limited to) developing more non-emissive energy, improving algal growth and bioengineering algae for improved growth rate, yield and decreased nutrient demand. However, once we have produced algal biomass we must also figure out how to store it. This is a thorny problem because many modes of storage will be “leaky” - resulting in the loss of carbon as methane or CO2 due to bacterial metabolism, for example. As usual, more research is needed…

Composition of algal biomass

In order to know how much algae to grow, we need to know what the algae is made of. Here I will assume that all the carbon in algal biomass comes from atmospheric CO2 fixation - this is true for any algae we would choose to grow. As such, we can figure out how much algal mass we need by calculating how much carbon is in it.

| E. coli | Synechocystis PCC 6803 | C. reinhardtii | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon | 44.3% | 51.4% | 48.1% |

| Hydrogen | 7.4% | 6.8% | 7.3% |

| Nitrogen | 12.1% | 11.3% | 5.8% |

| Oxygen | 28.0% | 27.5% | 5.8% |

| Reference | BNID 111459 | BNID 105530 | BNID 105933 |

Synechocystis PCC 6803 is a model cyanobacterium (a green, chlorophyll-using photosynthetic bacterium) and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii is a model eukaryotic alga. E. coli, in contrast, is not photosynthetic but heterotrophic i.e. eating organic compounds like sugars in order to gain energy and carbon for its maintenance and reproduction. You might have thought that the photosynthetic organisms would have a lot more carbon in them than E. coli because they fix carbon for a living and might need to store it. Indeed their biomass is somewhat more enriched in carbon than E. coli’s but not substantially so. Based on the numbers in the table above I will assume that dry algal and cyanobacterial biomass is ~50% carbon by weight.

How much biomass?

Humans are responsible for roughly 40 gigatons of CO2 emissions per year (IPCC AR5 Report). 1 gigaton (Gt) is \(10^9\) metric tons and 40 Gt is an incredible amount - \(40 \times 10^{12}\) kg or roughly \(90 \times 10^{12}\) pounds of CO2. To give you a sense of scale, a male African elephant ways ~ 5 tons, so 40 Gt is the mass of 8 billion adult male elephants. Total emissions (i.e. including N2O, methane, fluorocarbons etc.) are on the order of 50 Gt CO2 equivalents a year (10 billion elephants, IPCC AR5 Report). These CO2 equivalent units are useful here because they put the climate effects of different molecules into the same units as CO2. So if we fixed 50 Gt of CO2 in one year we’d effectively neutralize all human emissions (neglecting for now that we’d be incentivicing more emissions by doing so).

By mass, CO2 is 27.3% carbon. Therefore, we’d need to produce

\[50 \text{ Gt CO2} \times 0.273 \frac{\text{Gt C}}{\text{Gt CO2}} \times 2 \frac{\text{Gt Biomass}}{\text{Gt C}} = 27.3 \text{ Gt Biomass}\]or roughly 30 Gt of algal biomass per year to totally cancel human emissions.

How much energy?

Decades of algal biofuels research has focused on designing processes for low-cost and low-energy production of biological fuels from algal biomass. However, these processes are optimized for the production of fuel (from algal lipids) and not for the production of dry biomass for carbon storage. Moreover, life-cycle analysis of biofuel systems do not always straightforwardly report the energy cost of cultivation and harvest per unit biomass (the quantities of interest here since we are not considering making fuels) and there is considerable variability in estimated energetic costs of growing algal biomass when they are reported (see below). In some cases algae are grown under lamps and in other cases they are grown using sunlight alone. The estimates given below do not include the solar energy used by growing algae and so underestimate the total energy demand of algal growth. Since solar energy does not produce CO2 emissions this is fine for our purposes.

| Cultivation Mode | Growth Energy (kWh/kg) | Harvest (kWh/kg) | Note | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Raceway base | 66.9 | 18 | Real facility | Passell 2013 |

| Raceway future | 7.68 | 0.9 | Calculated from data given | Passell 2013 |

| Bioreactor | 2.0 | Harvest included? | Jorquera 2010 | |

| Raceway | 1.25 | Harvest included? | Jorquera 2010 | |

| Raceway | 0.2 | Harvest not included, uses flocculant | Campbell 2011 |

Research by Passell et al. 2013 gives a real-world analysis of a 1000 m2 flue-gas fed raceway system in Ashkelon, Israel. This relatively small system requires nearly 85 kWh of electricity to produce 1 kg of dry algal biomass. Their research suggests that technological improvements and economies of scale would reduce energy usage by roughly tenfold by using lower power mixing systems and induced flocculation to reduce energy required for drying the algae. Other studies come to much lower estimates but are not derived from real-world systems and are, as such, likely optimistic. Unfortunately I have not been able to find more analyses of real-world systems, so if you know of any such analyses please contact me.

I’ll assume a pessimistic base case where dry algal biomass can be produced for 50 kWh/kg (similar to the base case of Passel et al. 2013) and also analyze a “plausible case” of 5 kWh/kg and an “optimistic case” of 0.5 kWh/kg. In each case I report the total energy requirement as well as the percentage of 2017 world energy production (2017 WEP = 162820 TWh) and 2017 world non-emissive energy production (2017 WNEEP = 7634 TWh, data from IEA 2017 Key World Energy Statistics). Improvements in the efficiency of biomass production will likely come from improvements in process engineering (e.g. mixing, lighting, aeration & drying for less power) and biological engineering (e.g. higher yielding strains, inducible flocculation).

| Scenario | kWh/kg | TWh/Gt | TWh for 30 Gt | % 2017 WEP | %2017 WNEEP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pessimistic | 50 | \(5 \times 10^4\) | \(1.5 \times 10^6\) | ~900% | ~20000% |

| Plausible | 5 | \(5 \times 10^3\) | \(1.5 \times 10^5\) | ~90% | ~2000% |

| Optimistic | 0.5 | \(5 \times 10^2\) | \(1.5 \times 10^4\) | ~9% | ~200% |

Production of algal biofuels is typically estimated to be a net emitter of CO2 because it requires electricity. Electricity today nearly always draws on some emissive power sources except in some regions of the world where geothermal, solar or hydroelectric power are abundant. This is evidenced by the fact that > 65% world electricity came from coal, oil and natural gas as of 2015 (IEA 2017). For our purposes we would need to draw electricity from a non-emissive source like nuclear, wind, hydrothermal, etc. in order for the process to result in net fixation of CO2. Moreover, it may be challenging to use solar energy to produce electricity for algal growth because we will want to use the areas of Earth with the most sunlight to grow algae.

For this reason it is important to compare the energy demand of algal cultivation with the total amount of non-emissive power available. You can see from the table above that even in the optimistic case where we achieve roughly 100x improvement in the energy demands of algal cultivation there is not currently (as of 2017) enough non-emissive power generation on Earth to grow 30 Gt of algal biomass. To get a sense of how much total renewable power is available to us, note that there is approximately 6 kWh/m2 of solar energy incident on the Earth. Supposing we can only capture that energy on land (eliminating the ~70% of Earth’s surface that is ocean), that we do so only 8 hours/day and with only 10% efficiency (accounting for capture and transmission inefficiencies, land used for other purposes, etc) worldwide solar deployment would capture

\[6 \frac{\text{kWh}}{m^2} \times 0.3 \times \frac{8}{24} \times 0.1 \times 5.1 \times 10^{14} m^2 \simeq 3 \times 10^{13} \text{ kWh} = 3\times10^4 \text{ TWh}\]where \(5.1 \times 10^{14}\) is the surface area of the Earth in m2. A more detailed but ultimately consistent calculation can be found here. This is roughly double the amount of energy we would need in the optimistic scenario and does not account for nuclear, geothermal, wind or hydroelectric power generation all of which are already sources substantial sources of electricity, each producing > 100 TWh globally as of 2017.

In conclusion

Given the the current state of world affairs it is not possible to eliminate the climactic effects of human emissions by growing algae. This is not so surprising in retrospect - it makes sense that you’d need a planetary amount of energy to counteract emisssions generated by the whole human population of Earth from fuels accumulated over billions of years. However the picture is not really as bleak as it seems. First, it seems clear that techonological developments can make this approach much more viable than it appears today. Clever process engineering coupled with biological research and engineering could improve the rate and yield of algal growth so that my optimistic estimate above is realized. Moreover, technological improvements can and should be coupled with changes to policy - i.e. emissions reductions through changing behavior and power infrastructure - so that the scale of the problem does not increase as we develop solutions. Policy manipulation will be essential for any carbon capture strategy we pursue in order to avoid the obvious moral hazard - that people will be incentivized to emit more as we reduce the impact of their carbon emissions through capture systems. Laws and economic incentives must be used to counteract that hazard.

Importantly, nothing in this post touches on the long-term storage of biomass. This is a particularly thorny problem because many modes of storage are “leaky” - i.e. entailing loss of stored carbon as CO2 or methane. For every gigaton of carbon fixed each year by natural photosynthetic processes, a large fraction of it re-relased as a product of metabolism. In natural ecosystems more than 90% of gross photosynthetic fixation is re-released on a yearly basis. We would need to store algal biomass in a more stable form for this strategy to work. There are several promising methods for carbon storage (e.g. biochar is commonly cited) and they might be used in conjunction to maximize long-term storage of carbon.

Thanks to Sam Altman & Dave Savage for pushing me to do this calculation and to Yinon Bar-On for double checking it. If you have any comments, questions or data to share please contact me on Twitter.