#AviLovesYourPaper #1 - Jinich et al. PNAS 2020

This post was converted from a twitter thread from January 15th, 2021:

This week on #AviLovesYourPaper I re-read @champiDicty’s “A thermodynamic atlas of carbon redox chemical space” - a really pleasing application of recent advances in computational chemistry to probe the origin and structure of cellular metabolism.

Metabolism - the interconnected web of chemical transformations used by organisms to convert food in to usable energy and the chemical building blocks making up macromolecules of life - is surprisingly conserved. Bacteria, animals and plants use a lot of the same pathways and molecules despite enormous differences in how these organisms live, breathe, eat and reproduce. For example: that glycolysis pathway you may have memorized once.

Adrian Jinich and friends ask: is there anything special about this conserved set of biological molecules? In particular, is there anything about their thermodynamic properties that distinguishes them? The thermodynamic argument goes like this: some molecules are more “stable” than others and we expect them to accumulate over time. Here “stable” means something like “the reactions producing them occur more readily than the ones consuming them.”

Important note: @champiDicty recently developed a new quantum-chemical approach to estimating the thermodynamic stability of small molecules with impressive accuracy. journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/a…

Now if we imagine the amorphous prebiotic period before the origins of life, there must have been some molecules in the primordial soup for emerging life to latch on to and “boot up” the first metabolisms. It’s likely that these prebiotic molecules were “stable” in the thermodynamic sense as they must have accumulated before any cells, enzymes, or proteins. Similar logic animated the famous Miller-Urey experiments.

Other molecules are less thermodynamically stable, but stable in the colloquial (kinetic) sense: they don’t break down very quickly. These are good food sources as coordinated metabolic decomposition can harvest the energy stored in them. Carbohydrates, proteins, and fats are like this - thermodynamically unstable (high energy content), but very shelf-stable like of a bottle of vegetable oil.

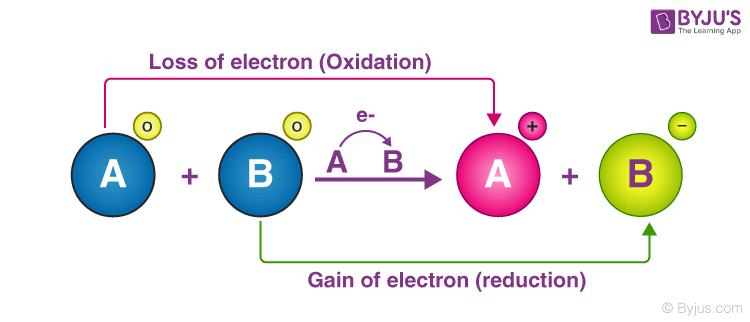

To understand the rest of this paper it must be said that many metabolic reactions are redox reactions involving the transfer of electrons, usually two electrons at a time, and usually coming along with a proton (a “hydride transfer”).

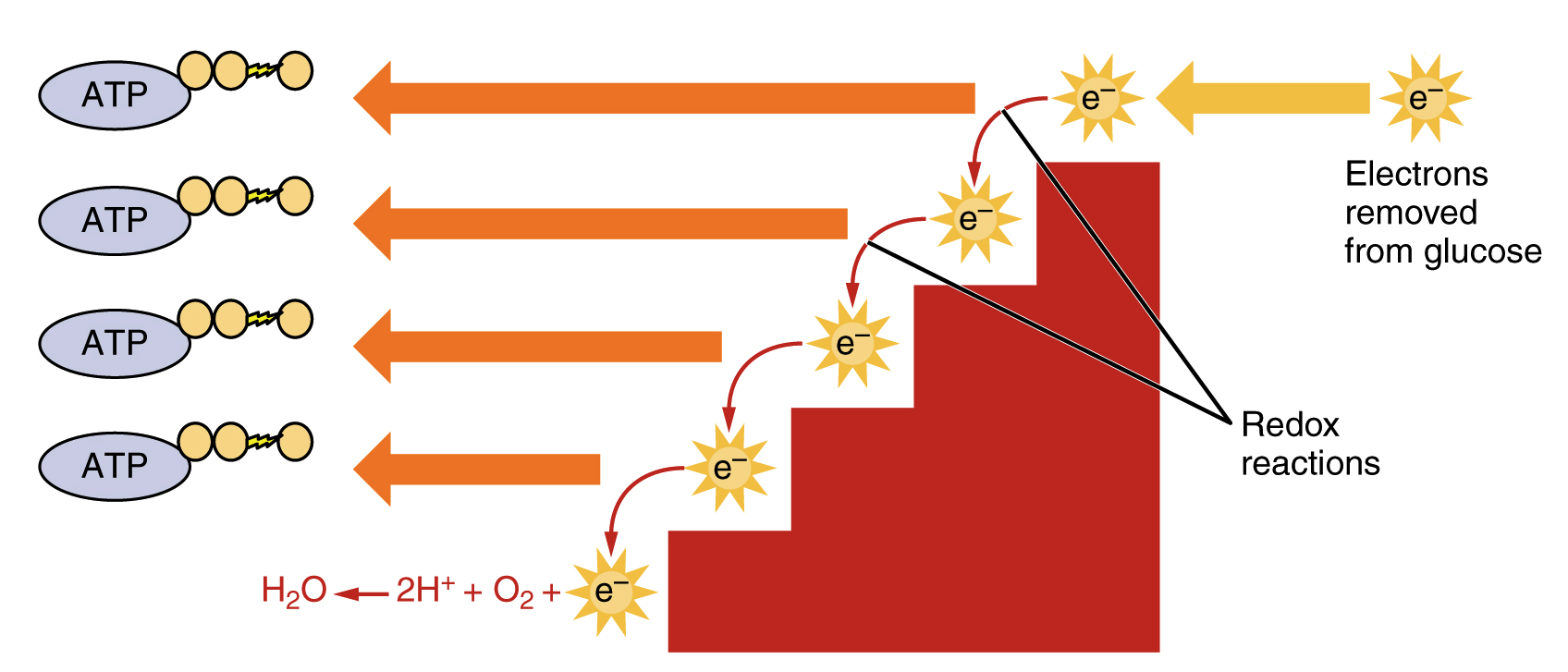

You can think of this by analogy to electricity. Current develops in a wire as electrons flow towards the positive terminal. Plugging our devices in harnesses the energy associated with electron flow. Similarly, metabolism “taps” the energy of electron movement by coordinating the flow of electrons from one molecule to another. This energy is usually stored by “coupling” electron transfer to production of ATP - an energy carrier molecule you probably memorized once.

Jinich et al. computationally generated a list of all the linear carbon-based molecules with 2, 3, 4, and 5 carbon atoms and all of the redox reactions interconverting between these molecules. Less than half of these molecules are known to be used by biology.

They used their new quantum chemical approach to ask: which of these redox reactions are favorable? and which of these molecules are most stable? Important point: redox reactions are favorable when the products are more thermodynamically stable than substrates. But since “electrons” are one of the the reactants, we have to know where the e- came from and where they are going - the electron “donor” and “acceptor”. Fortunately, we know a lot about e- donors and acceptors in contemporary biology (remember NADH?) and have good ideas about prebiotic times. This allows Adrian & co. to calculate the stability of carbon-based molecules across a variety of biologically-relevant conditions.

What they find is pleasing: biological molecules, i.e. molecules participating in metabolism, are generally more stable than non-biological ones across a range of conditions. Here blue is “stable” and red “unstable.”

Biological molecules were also more water soluble than non-biological ones on average, and less likely to contain (toxic) aldehyde groups than would be expected by chance, consistent with previous research.

One set of biological molecules, aldose sugars like glucose (6 carbons), ribose (5C), erythryose (4C) and glyceraldehyde (3C) are frequently used in metabolism but not very stable. However, due to their chemistry and asymmetry, aldose sugars are especially well-connected to other molecules via redox reactions, which could explain why sugars are often used as energy storage by plants (starch), animals and bacteria (glycogen). Reminds me of another paper I like… sciencedirect.com/science/articl…

All told, I found this paper to be a very satisfying capstone. Not only of Adrian’s PhD research calculating the stability of biological molecules, but also a much longer thread of researchers studying the chemical principles of metabolism. I know that our dear friend and mentor Arren Bar-Even would have been proud to read this work. Though Arren passed away very unexpectedly in September, his influence is inscribed clearly and deeply on this work. @WeTheBarEvenLab /fin