Writing

Contents

Online Resources

-

“eQuilibrator, the Biochemical Thermodynamics Calculator.” An online tool for calculating thermodynamic potentials of biochemical reactions using free-text search. Development ongoing with Elad Noor.

-

“Classic Reactions” - a primer on the basics of metabolism from a thermodynamic perspective. Housed on eQuilibrator and written with help from Elad Noor, Noam Prywes, Dave Savage and Ron Milo.

-

“Human Impacts Database. Developed primarily by Griffin Chure as part of the Human Impacts project in Rob Phillips’ group, which I contribute to.

-

“Avi’s Faves” Poems my friend Andrew thinks I like. He is mostly right.

Academic Writing

These are my faves. Find a full listing on Google Scholar

Primary Research

“The proteome is a terminal electron acceptor.”

Today, two distinct frameworks are used to study microbial growth. One approach treats microbes as chemical agents, performing redox chemistry to conserve energy and assimilating nutrients (C, H, N, O, P, S) to form biomass. Another model describes the allocation of cells’ finite biosynthetic capacity to different catalytic roles — e.g., transport, protein synthesis — to achieve particular metabolic rates. These frameworks have distinct strengths: redox naturally describes a diversity of metabolic chemistries, while resource allocation explains the existence of intrinsic maximum growth rates, for example. In this preprint we introduce a unified redox-based resource allocation model that links physiology to environmental chemistry. This integration is conceptually useful — offering concise explanations for key microbiological phenomena — and also predictive — uncovering an unexpected mode of sequence evolution wherein proteins are selected for their ability to participate in the redox chemistry of metabolism, i.e. for their ability to serve as a terminal electron acceptor.

“Annotation-free prediction of microbial dioxygen utilization.”

We now have access to sequence data from a wide variety of natural environments. These data document a bewildering diversity of microbes, many known only from their genomes. We now know that physiology – an organism’s capacity to engage metabolically with its environment – often provides a more useful lens than taxonomy for understanding microbial communities. As an example of this broader principle, we developed algorithms that accurately predict microbial dioxygen utilization directly from genome sequences without annotating genes, e.g. by considering only the amino acids in protein sequences. Annotation-free algorithms enabled rapid characterization of natural samples, highlighting quantitative correspondence between sequences and local oxygen levels in a dataset from the Black Sea. This example suggests that DNA sequencing can be repurposed as a multi-pronged chemical sensor, estimating concentrations of oxygen along with other key facets of complex natural settings.

“Closed ecosystems extract energy through self-organized nutrient cycles.”

Life on Earth relies on sunlight for energy, but this energy can only be exploited through the collective recycling of matter by communities of microbes, plants, and animals. Despite these basic facts of life on Earth, we currently lack a framework for understanding how ecosystems can organize themselves to collectively capture the sun’s energy. In this paper, led by Akhit Goyal and Arvind Murugan, we advance a conceptual model to study the collective properties of nutrient-recycling ecosystems. Surprisingly, even though species “greedily” extract energy from the environment, sufficiently diverse communities of species almost always manage to sustain themselves by extracting enough energy. Further, the amount of energy extracted by these self-organized communities is close to the maximum possible and much greater (≈100x) than extracted by random collections of species.

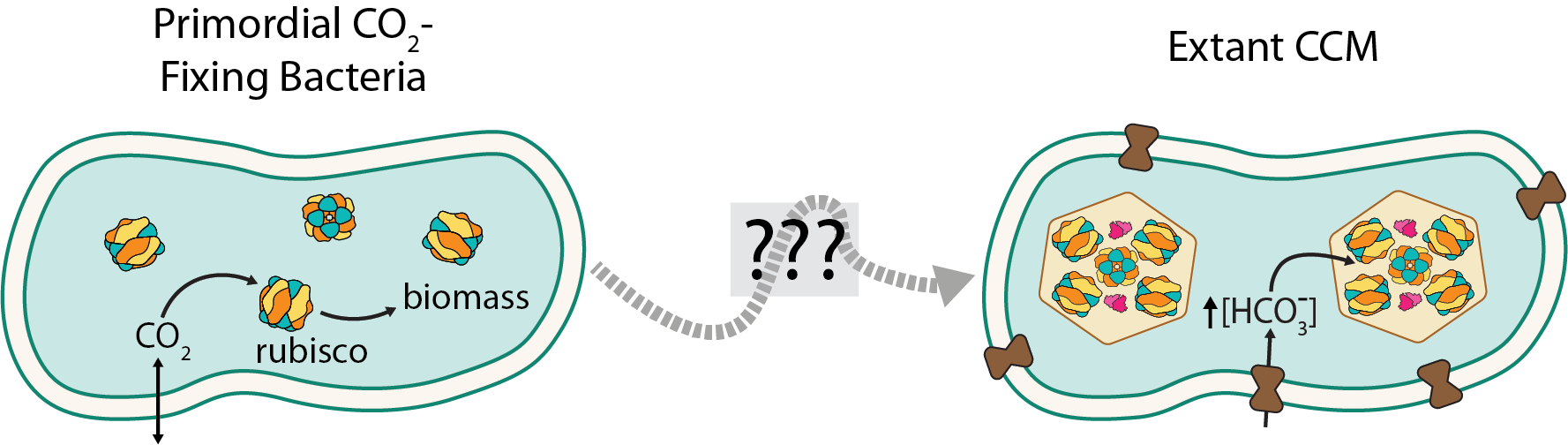

“Trajectories for the evolution of bacterial CO2-concentrating mechanisms.”

Working with several friends, including my amazing technician Eli Dugan (now at UCSF), I studied the evolution of a complex, multicompenent system called the bacterial CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM), which enables all modern Cyanobacteria to grow robustly in today’s atmosphere. The CCM is so tightly-integrated into host bactera that mutants lacking any one of ≈15 genes coding for core CCM components fail to grow in today’s atmosphere (≈0.04% CO2). If every piece of the CCM is required for its modern function, how could it have evolved? In this paper we used the tools of synthetic biology to “resurrect” ancestral forms of bacterial CCMs by engineering modern bacteria to resemble ancient ones. Our experiments helped us understand how CCMs might have evolved in a piecemeal fashion by accruing individual components over billions of years as Earth’s atmosphere was slowly changing. Collaborating with Woody Fischer (Caltech Geobiology) on this research deepened my interest in Earth science and paved the road to my postdoc at Caltech. Read more here.

“Optical O2 sensors also respond to redox active metabolites commonly secreted by bacteria.”

While my PhD was focused on bacterial photosynthesis, I turned to the other arm of the biological carbon cycle during my postdoc - respiration. While photosynthesis makes organic molecules from CO2 and water by harnessing the energy of light, respiration uses the energy of O2 (its tendency to take electrons) to break those same molecules down, piece by piece, forming CO2 again. I tried to measure the respiratory rates of single bacterial colonies to understand how “microenvironments” are formed and maintained. In doing this, I encountered challenge that was not documented in the literature: many bacteria secrete molecules that greatly interfere with optical O2 sensors. This paper documents the problem and also offers two avenues to solve it. First: some bacteria, e.g. E. coli, secrete no problematic molecules. Second, it matters what the sensors are made of. Materials engineering might protect optical nanosensors from interference by bacterial secretions.

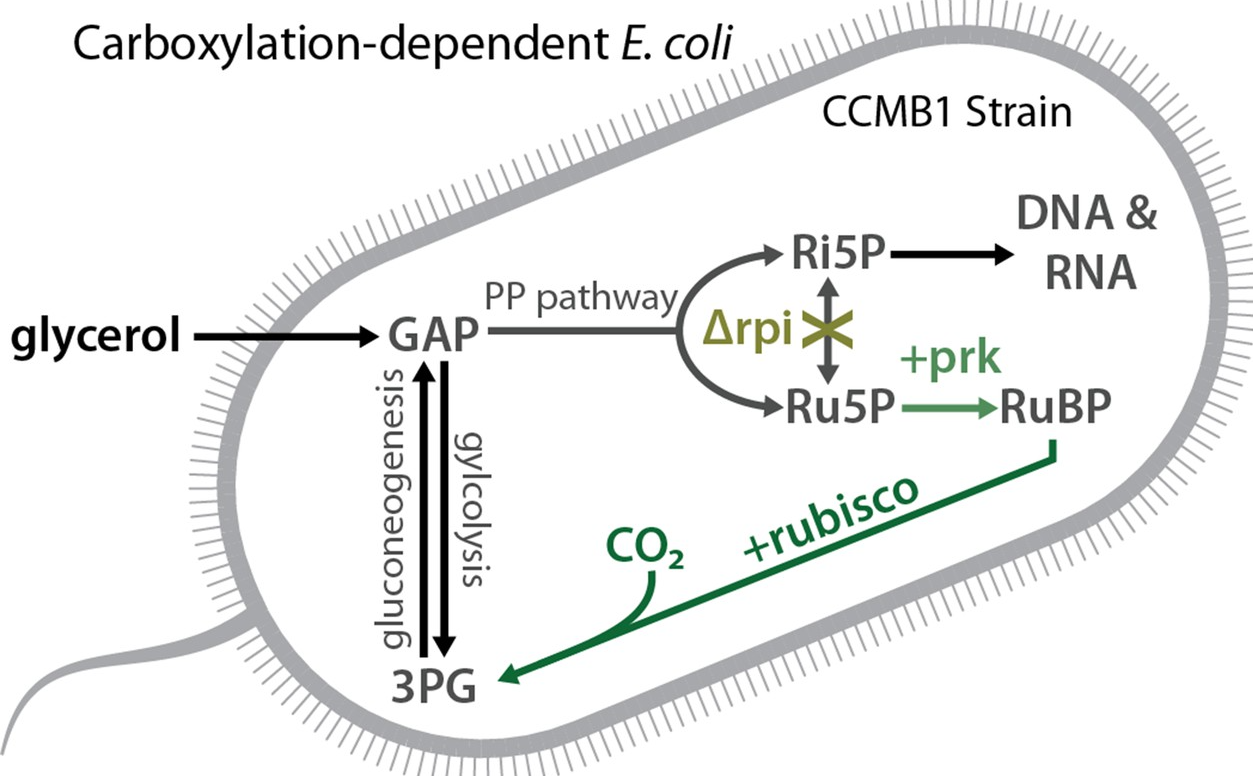

“Functional reconstitution of a bacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism in E. coli”

Many photosynthetic organisms have evolved CO2-concentrating mechanisms (CCMs) that compensate for the relative inefficiencies of carbon fixation by elevating CO2 levels near the central enzyme of the Calvin cycle, rubisco. Elevated CO2 is doubly beneficial, bringing rubisco closer to CO2-saturation and also excluding O2 from the active site (explained here). CCMs are very significant on the global scale, responsible for perhaps 50% of global photosynthesis. CCMs are also very significant to the organisms harboring them: CCM mutants typically entirely fail to grow in ambient levels of CO2 (0.04%) and require CO2 supplementation to enable robust growth (usually 1-5%). In this paper I paid homage to Richard Feynman’s famous quote “What I cannot create I do not understand” building a bacterial CO2-concentrating mechanism from its constituent parts in a non-native host, E. coli. Read more here.

“Revisiting tradeoffs between Rubisco kinetic parameters”

All plants, algae and cyanobacteria rely on the Calvin cycle for growth. Rubisco is the central enzyme of the cycle and the most abundant enzyme on the planet: it does the tricky bit where CO2 gets “fixed” onto a soluble sugar. While it is often said that rubisco is “slow,” it is actually an average enzyme in terms of “turnover number” (maximum rate per active site, kcat). The true rate of rubisco carboxylation is much slower than its kcat, however, because rubisco can react non-specifically with O2. I certainly think it’s surprising that rubisco is not faster or more specific given how important and abundant it is.

Why isn’t rubisco faster? Why isn’t it more CO2-specific? It’s often argued that rubisco can’t be both fast and specific. Correlations between rubisco kinetic parameters are taken to support this argument since they show that faster rubiscos are less CO2-specific. But these arguments were based on a small dataset (about 20 rubiscos). We collected a much larger dataset and found that most correlations are now substantially weaker, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the factors limiting the evolution of this pivotal enzyme. Read more here.

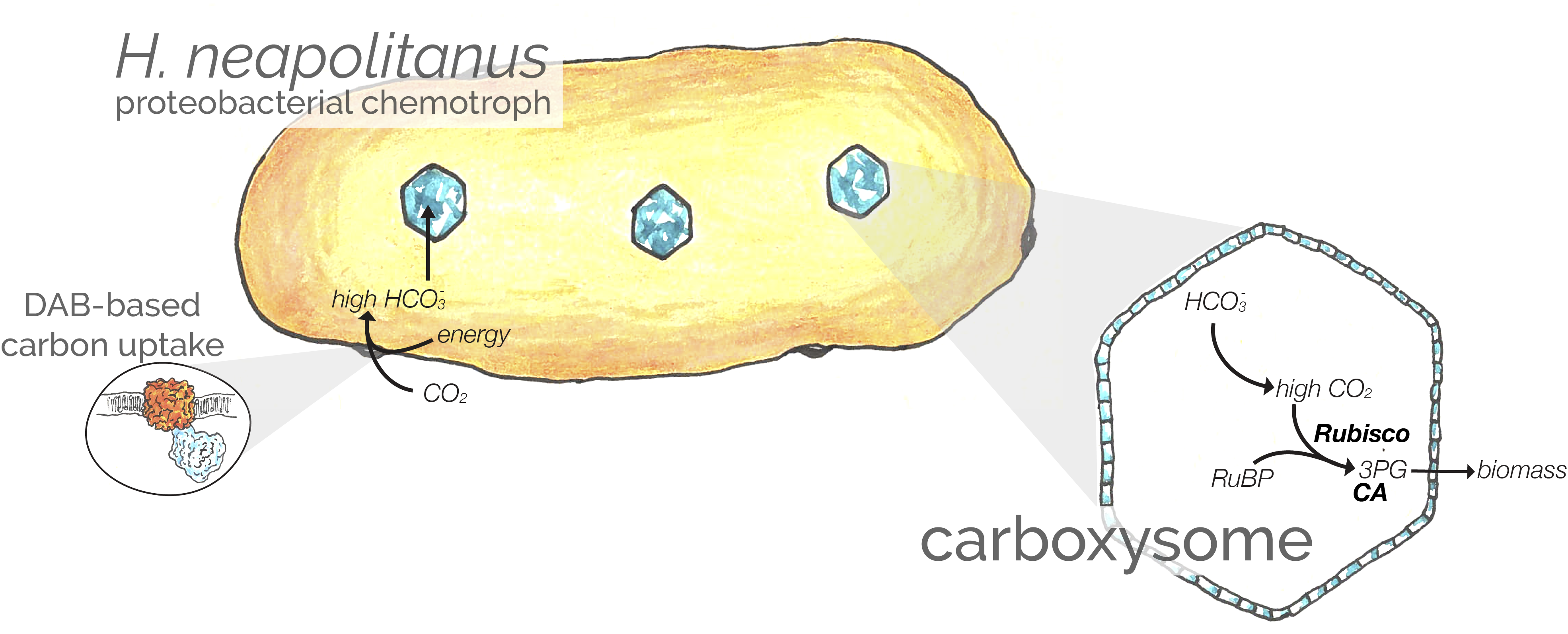

“DABs are inorganic carbon pumps found throughout prokaryotic phyla”

When I started my PhD studying the carboxysome-based CO2-concentrating mechanism (CCM) found bacteria, it was unclear if we knew all the genes making up this exquisite photosynthetic adaptation. We thought about 15 genes were involved, but it was conceivable that the number was much higher. Our goal here was to determine (i) whether unknown genes are required for the CCM and (ii) which genes perform the essential inorganic carbon transport activity. Using a barcoded approach to TNSeq called RB-TNSeq, we investigated 70,000 knockout mutants in the bacterial chemoautotroph, H. neapolitanus. We found that at most 17 genes are necessary for this organisms’ CCM to function. Building on three recent papers from Kathleen Scott, we also showed that a pair of genes - DabAB2 - are necessary and sufficient for inorganic carbon transport. We think the data imply that DABs are two-protein complexes that convert extracellular CO2 into intracellular HCO3- using an energy-coupled carbonic anhydrase-like mechanism. Read more here.

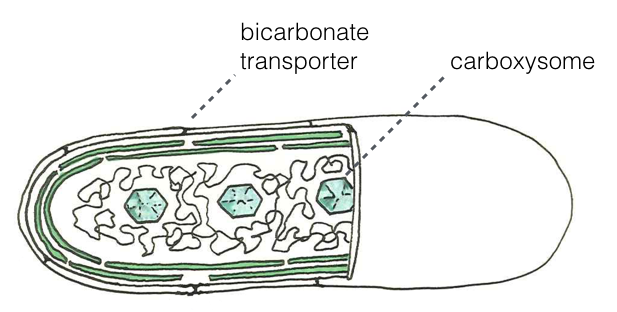

“pH determines the energetic efficiency of the cyanobacterial CO2 concentrating mechanism”

Cyanobacteria are the ancestors of all oxygenic photosynthesis on the planet and all cyanobacteria have a carboxysome-based CO2 concentrating mechanism (CCM). Many labs are interested in transplanting the cyanobacterial CCM into crop plants in order to improve their growth. Here we show that any reasonable description of the CCM must account for the enormous effect that pH has on the composition of the inorganic carbon pool both inside and outside cells. Once we account for the pH fully, we can produce a mathematical description of the CCM that is consistent with measurements of cyanobacterial physiology and biochemical intuition on multiple levels. A long-term collaboration with Niall Mangan with lots of help from Rachel Hood, Ron Milo and David Savage, PNAS 2016.

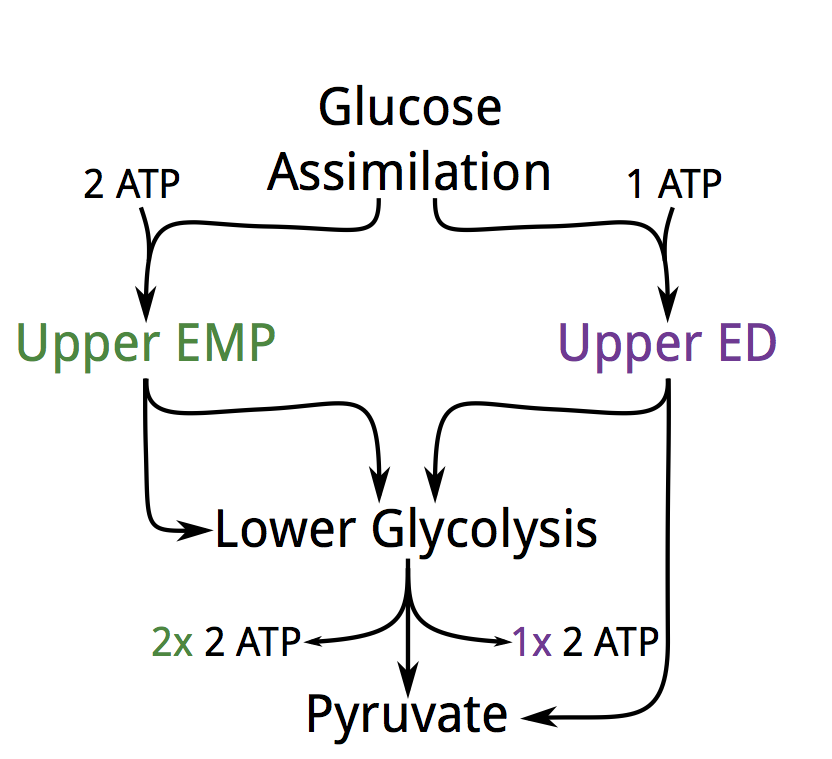

“Glycolytic strategy as a tradeoff between energy yield and protein cost”

Offering a possible thermodynamic explanation for why so many bacteria appear to use non-canonical glycolytic pathways, especially the Entner–Doudoroff (ED) pathway. The textbook Embden-Meyerhoff-Parnass (EMP) pathway yields 2 ATP per glucose while most non-canonical pathways yield less. Naively we’d expect that cells should switch to higher yielding pathways, but they appear not to. Lower yield pathways are more thermodynamically favorable which, we suggest, makes them more suited to carrying high flux. I was incredibly fortunate to collaborate with Elad Noor in this work, with major contributions from Arren Bar-Even, Wolfram Liebermeister and Ron Milo, PNAS 2013.

Arion Stettner and Daniel Segre wrote a nice commentary on our work here. This paper - Fuhrer et al. J. Bac 2005 - from the Sauer lab at ETH was a major motivation for this study. Subsequent to our paper, elegant experiments have shown that the ED pathway is likely present in plants and cyanobacteria (Chen et al., PNAS 2016) and is a major route of bacterial degradation of sulfate-substituted sugar acids that derive from plant membranes (Felux et al., PNAS 2015).

Commentary and Framing

“Matching metabolic supply to demand optimizes microbial growth”

Recent research has strengthened the notion that microbes allocate their biosynthetic capacity to maximize the growth rate. Yet many microbes can grow substantially faster after laboratory evolution. Here Akshit Goyal and I comment on a resource-allocation model from Chure and Cremer, which they derive from first principles, that offers resolution to this conundrum.

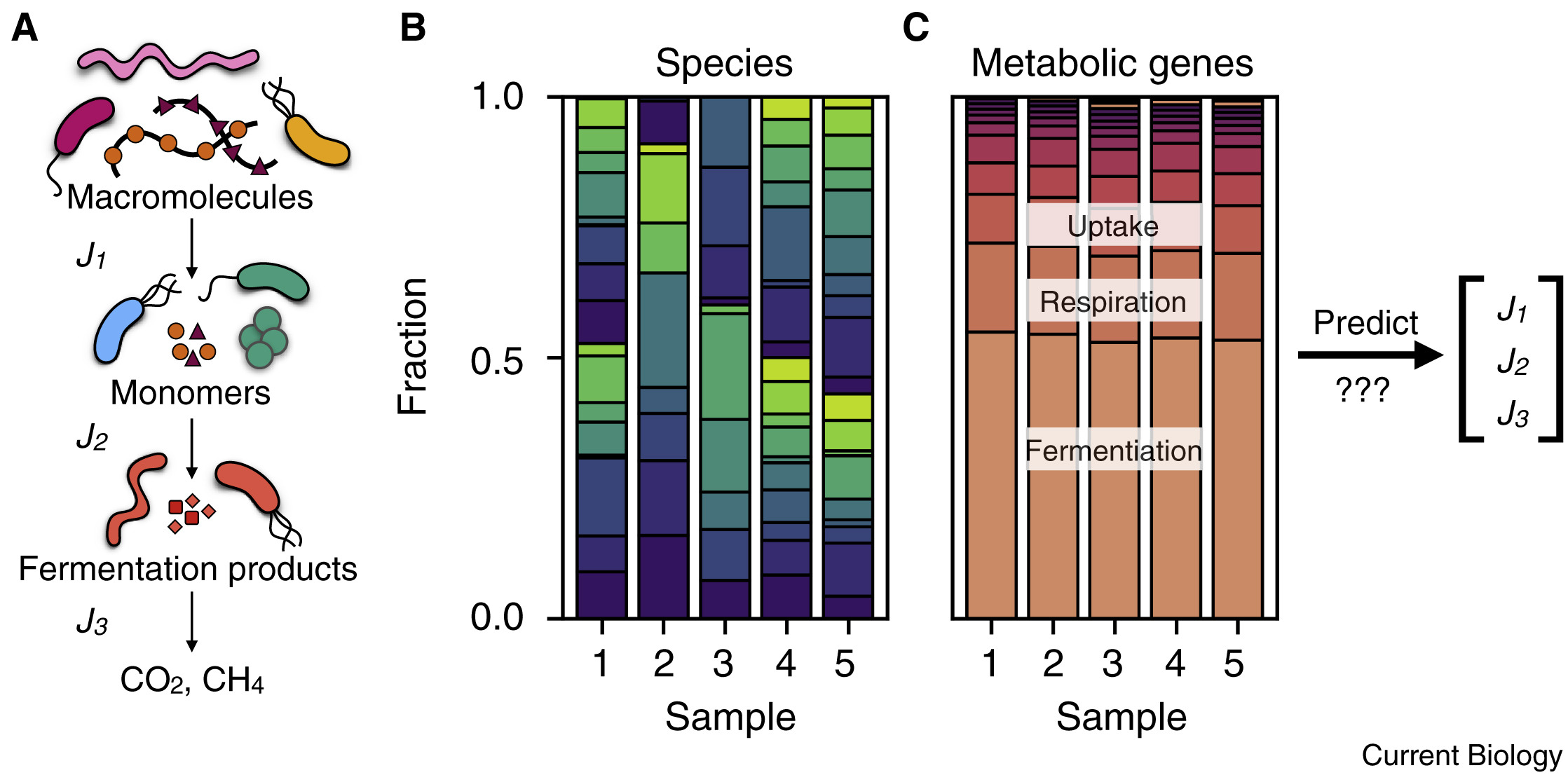

“The metabolic rate is the trait”

Making sense of the metabolism of microbial communities is a daunting, yet vital taks. Vital because microbes catalyze many critical chemical transformation that recycle elements like carbon, oxygen, sulfur, and nitrogen, supporting the entire biosphere by making them available for reuse. It is vitally important that microbes keep doing us this favor, even as the climate changes and environments change with it (e.g. ocean acidification). Yet there are more than a trillion-trillion-trillion microbes on our planet (≈1030) representing roughly a million species. A single gram of soil might contain 1000 species and a trillion individual bugs. How could we possibly understand and predict something so complex? With my mentor, Dianne Newman, I offer commentary on a promising approach described in an excellent paper by Karna Gowda and colleagues. Karna et al. broke ground on an optimistic hypothesis - that communal metabolic rates can be predicted from gene content of natural environments. If this optimistic hypothesis is to be true for soils, then it must also be true in the lab. Karna & friends used bacterial denitrification (nitrate “breathing”) to learn how to compose predictions of microbial metabolic rates from genome sequences and a small number of lab measurements, achieving surprising quantitative success.

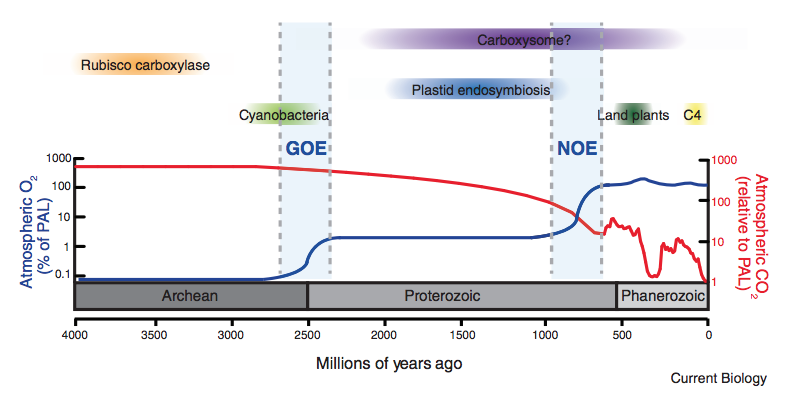

“Cell biology of photosynthesis over geologic time”

Though atmospheric CO2 concentrations are today rising precipitously, geologic processes like rock weathering have, over billion-year timescales, led to substantial reductions in atmospheric CO2. At the same time, the emergence of oxygenic photosynthesis led to a build up of O2 in Earth’s atmosphere, which is problematic for organisms relying on rubisco to fix carbon. In this primer, Patrick Shih and I reflect on how these two trends might have conspired to promote the evolution of novel photosynthetic physiologies (several types of CO2 concentrating mechanisms) that enable photosynthetic organisms to cope with low levels of the growth substrate (CO2) and high levels of inhibitor (O2). We describe how these physiologies differ between photosynthetic bacteria, algae and land plants and suggest that these differences might not be coincidental (i.e. no “frozen accident”).

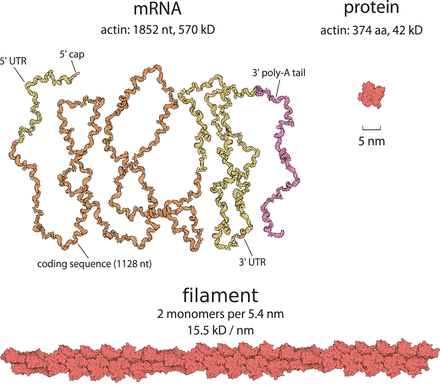

“The Quantified Cell”

A prelude to Cell Biology by the Numbers on the importance of attaching numbers to biological phenomena, for without them we are just guessing wildly. We use the example of actin-based motility to show how quantitative reasoning can be used to link diverse studies together and draw inferences about cell physiology. We would argue that all hypotheses should be quantified because the process forces you to confront what you do not know and what you cannot reasonably approximate. With Rob Phillips and Ron Milo, Molecular Biology of the Cell 9.2014.

“A note on the kinetics of enzyme action: a decomposition that highlights thermodynamic effects”

Pointing out that ideas from non-equilibrium thermodynamics can be used to rewrite a typical Michaelis-Menten enzymatic rate law to include a thermodynamic term expressing the displacement from equilibrium. This functional form has several advantages over the usual Michaelis-Menten framing. First, it accounts for the effect of the “flux-force relation” where reactions near equilibrium require more enzyme to catalyze the same net flux because much of the enzyme is “wasted” catalyzing the reverse reaction. Second, in the usual Michaelis-Menten form, you must ensure that kinetic parameters are consistent with equilibrium constants (i.e. conform to the Haldane relation). Our strategy “cooks-in” compliance with Haldane by omitting some kinetic constants and instead determining them implicity from the equilibrium constants. Finally, measurements of equilibrium constants are much more available and broadly applicable than measurements of enzymate rate constants, which are gene-specific and often unavailable. Primarily the work of Elad Noor with some help from myself, Wolfram Liebermeister, Arren Bar-Even, and Ron Milo. FEBS Letters 2013.

“Rethinking glycolysis: on the biochemical logic of metabolic pathways”

Explaining how central biochemical constraints limit the space of plausible glycolytic pathways. We consider how toxicitiy and permeability of metabolites as well as chemical feasibility and thermodynamic favorability of enzymatic mechanisms define a very small number of pathways for glucose metabolism (many of which are similar). A nice contribution of this work is the framing of non-oxidative (i.e. fermentative) metabolism as a process of “internal electron rearrangement” where one moiety within a molecule becomes reduced at the expense of oxidizing another. Knowing which of these transfers are favorable can help rationalize many metabolic pathway’s structure. I really enjoy using these lines of reasoning in teaching. Primarily the work of Arren Bar-Even with some help from myself, Elad Noor and Ron Milo. Nature Chemical Biology 2012.

Public Writing and Talks

-

“Urbanism and Bike Share Maintenance” a review of the Lyft-owned East Bay bike share service. Berkeleyside 10.2019

-

“Bike Boulevards are Fiction” on the joke that is Berkeley bike infrastructure. Berkeleyside 5.2019

-

“An Interview with Geobiologist Woody Fischer” on the transformative effects photosynthesis has wrought on the Earth ecosystem. The Hypocrite Reader 10.2016

-

“An Interview with George Fox” on the evolution of life, the ribosome and the potential for alien inoculation of Earth. The Hypocrite Reader 12.2015

-

“Understanding the Greenhouse Effect from Classic Experiments” on the basic mechanism of the greenhouse effect, which we’ve understood for over 100 years. Nerd Night East Bay 5.29.2017